Speaking with the Dead: Life and Learning in a Cadaver Lab

It was winter 2008 when I first dismembered a human body.

By dismember, I really ought to say, “disarticulated the shoulder girdle from the axial skeleton by disconnecting the sternoclavicular joint and points of muscular attachment.” The former seems more concise –if not more gruesome– while the later is a mouthful in mixed company.

The fact is, when you find yourself disconnecting a limb from the body of a deceased human being, you are set upon by the immediate and unsettling notion that there are only two types of people who ever do such a thing. You sincerely hope that you fall closer to the “professional” end of that spectrum than the necrosadistic side. You see, I’m not a doctor; I am an artist and the study of human anatomy has been an ongoing pursuit throughout my career.

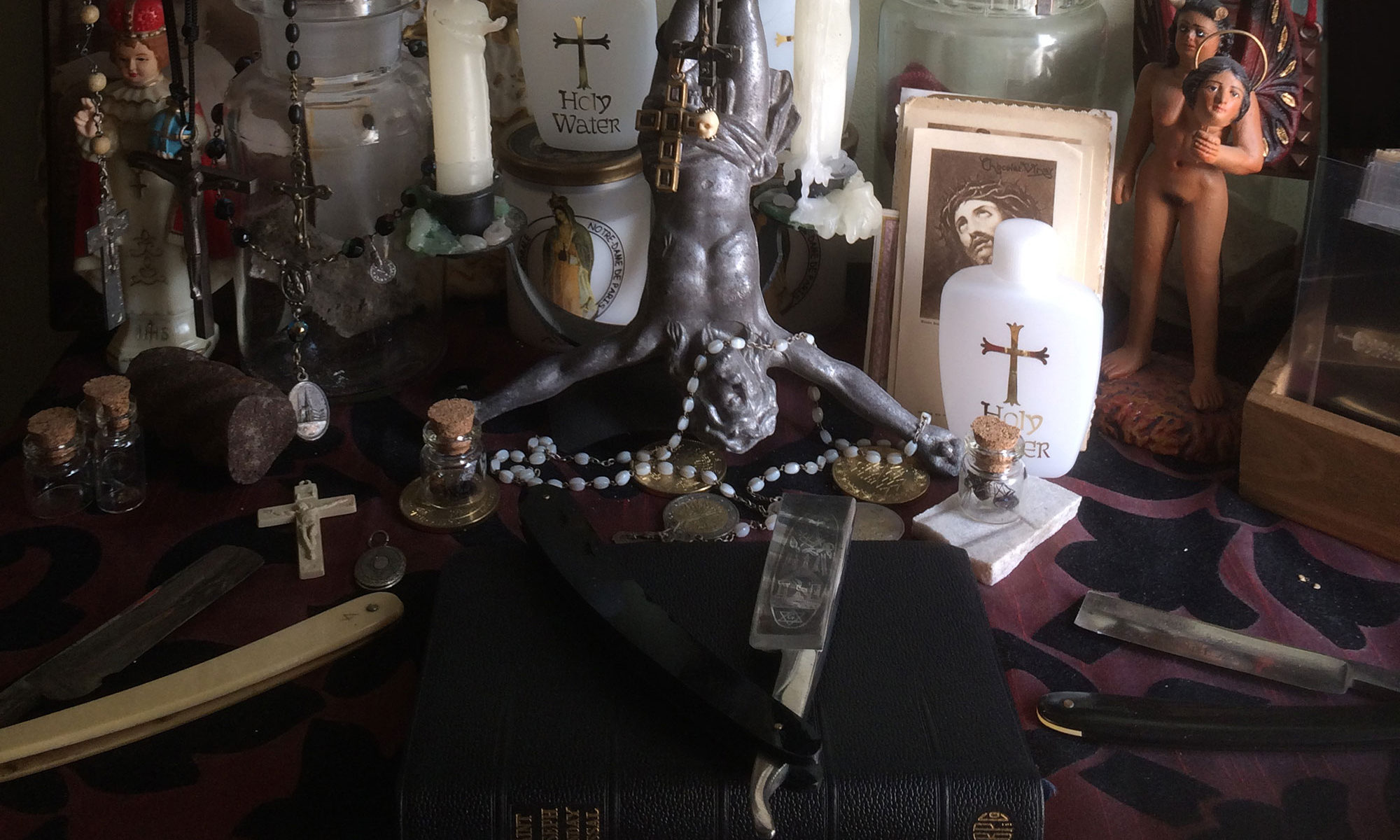

Hundreds of years ago, artists risked the Inquisition for access to human cadavers against the edicts of the Catholic church. Even today, there is no denying a powerful taboo lurking beneath the surface when you first confront a deceased human with the intention to cut it open and explore the inner workings. Even when you are operating in the professional confines of a medical school classroom, the experience can be wholly transformative on a professional, as well as a deeply personal, level.

In the winter of 2008, I was actively researching and writing a book on sculpting and human anatomy for a company that specialized in creating educational products for the artist market. My employer had previously worked with an anatomy lab in the midwest. He arranged for me to spend a week there working with the specimens in the medical school. With a strange tincture of dread and elation I boarded the plane to Utah.

Being mid-December, the halls of the school were almost entirely empty. It was simultaneously serene and unsettling to walk the deserted campus. In the entrance hall of the main medical building there was a small specimen museum for the students. Various human body parts sat inside Perspex tanks suspended in an amniotic formalin dreamworld. They were beautiful to behold. It would be a few days into my own experience of removing fat and fascia to expose the muscles beneath, that I could come to see just how elegantly executed those prosected specimens really were. It takes a deft touch and an expert eye to produce wet specimens such as these.

My employer and I walked through the snaking empty halls, our footfalls echoing through the linoleum passages until we came to a nondescript door marked A104. A strange feeling came over me as entered that room. I felt, for a moment, that I had come upon the precipice of something truly magnificent. it was not at all dissimilar from the sense of Kantian sublime I might feel entering a great Cathedral of Europe. This was indeed, a church. I was silent, looking around tentatively, unsure of what my next action should or could be. The room was slightly cooler than the rest of the building had been; a rather large classroom space filled with about 15 gurneys. On each of them was a vaguely human form shrouded in white fabric and an outer shell of thick clear plastic sheeting.

“Just pick someone and get started. I will find you a lab monitor,” my employer said, as he went toward a door at the back of the room. I was frozen in place. It occurred to me that I’d expected to be part of a class and following the guidance of an experienced professor. I had no idea how to begin. My mind was beset with questions. Can I do this? Should I do this? A million doubts rushed in on me, only to be broken by the sudden entry of a lab monitor. She was about 20, moving with the speed and confidence of someone well-versed in every aspect of her space and her job.

“Hey! Welcome,” she said. “So, just pick a body and go.” She opened a white cabinet and pulled out several objects, setting them down on the nearest gurney beside a pair of plastic sheathed legs. Her confidence put me at ease.

“I’m not exactly sure how to start,” I said. She smiled reassuringly. “Ah, then let me show you what you need to know!” She took a few moments to guide me though the basics, procedure and tools, and most importantly how to change a scalpel. This is invaluable information when it comes to a blade that can take your finger in a single inattentive instant.

After a quick, but thorough, tour of the tools and procedures she paused. “Ah! You will need this,” she said, taking a spiral bound book down off a nearby shelf. It was large and colorful with with a photo collage of dissected human body parts on the cover. In bold script letters the title read, “Grant’s Dissector.”

“What’s this?” I asked.

“That is the manual!” she replied brightly.

She quickly moved toward the exit, offering a hand if I needed anything else. I was surprised to discover that I was starting to feel a strange sense of anxiousness I hadn’t considered before. These were human bodies. The postmodern philosopher Julia Kristeva says that cadavers represented the ultimate abjection; the purest expression of that which we avoid and flee from as humans. In the face of this profundity I felt a touch of guilt for not being a surgeon in training; for not being a Michelangelo or an Artemisia Gentileschii. Did my worth as an artist merit this?

Most medical students have the benefit of processing their reactions to anatomy lab among peers. There’s an opportunity to compartmentalize, joke, be serious, to focus on the work at hand, and come to an understanding of the gravity of the gift these people left us. Being alone in the lab granted me greater freedom, but it also left me dealing with the very real and profound humanity of the situation on my own and without the benefit of a group dynamic.

I took a moment to look through the various bodies in the room, delicately unwrapping the heavy plastic sheets and the white bed linens underneath. Many had been flayed already and their body cavities emptied. Apparently, the anatomy classes had focused on the major arteries and nerves, as well as excavating the body cavity. The superficial layers of muscle were exposed and the deep layer undisturbed. This was ideal, as my focus was the superficial to deep layer of muscle anatomy and I would have the opportunity to look at these structures intact.

I unwrapped a large form in the middle of the room. He was an athletic man of about 50. I felt a sinking sadness for this man who died relatively young, whilst obviously taking good care of himself. The faces of the bodies are all wrapped separately for discretion and dignity. I tenderly unwound the fabric from his face. I felt a strange need to see him, to know what he looked like; to put face to this grief I felt for a perfect stranger. When I unwound the wraps, I found his face intact and undissected with the soft tissues of his flesh slightly plasticized by the embalming process. On the side of his forehead was a small deep contusion. It looked like a point of impact. I carefully covered his face and wrapped him back in his sheets and plastic to rest quietly.

The other bodies were considerably older men and women. Some specimens had seen more use than others. Over time the muscles can start to look shockingly similar to beef jerky as they dry out from exposure to air. To combat this we are supplied with a spritzer bottle of formalin –a modern replacement for the highly toxic formaldehyde. This is used to keep the exposed tissues preserved as you work. The hands and feet of all the bodies were also in little socks, soaked in chemicals to keep the muscles pliable and soft. There was something touching and a little sad about seeing a flayed cadaver with little white footie socks on.

I decided to work with an elderly man in the corner of the room. It was a choice that I made by feeling who seemed the most comfortable; who invited me to work with them. Over the course of the week I spent in the lab, I found myself alternately anthropomorphizing and disconnecting from the bodies. I found I could not effectively work if I maintained too close a proximity to the sense of the cadaver as a person. Other times, as I worked, I found myself being sure to treat the body gently and to turn him slowly and kindly. They were never just objects to me. If I were to disconnect and never again engage with their humanity, I would do a grave disservice to their generosity.

Following the instructions in Grant’s Dissector, I removed the flesh of the leg by making a series of incisions and a puncture unto which I could insert my finger. This facilitated peeling back the flesh in a process called “degloving.” As the flesh is removed you must carefully scrape away the subcutaneous fat and fascia underneath. Fat and fascia are everywhere beneath the skin. Fat tends to look like wet popcorn and it is present in every nook and cranny of the body. Depending on how heavy the person was in life, it can even be between muscles and inside the body cavity. The skill required to cleanly and efficiently remove both left me with a much deeper respect for the prosected specimens on display outside the lab.

Fascia looks like a fine layer of spiderweb over the muscles. You use tweezers to pick it up then detach it from the muscle gently with the scalpel. It’s a tedious and time consuming process and you must be very careful not to nick or damage the muscle tissue with your very sharp scalpel blade. Every time you think you have all the fascia, another layer seems to materialize. Fascia is essentially a connective tissue barrier that attaches, stabilizes, encloses, and separates muscles and organs. It can be quite a beautiful thing to observe.

Over the process of working with the cadavers, I was struck by how much never translates into anatomy books. I had studied anatomy books for years up to that point; from 100-year-old volumes with hand drawn plates to modern photographic editions complete with axial MRI scans. None of them captured the nuances and beauty of the human body as seen in person. One particular feature leapt out at me. The tendinous bands in the body, those flat bands of tendon that extend from the belly of the muscle to the ends, have a shimmering quality not unlike mother of pearl, and a pronounced iridescence that’s nearly impossible to photograph. I found myself taken aback many times by this beautiful shimmering hidden inside the body. It’s the proverbial difference between the map and the territory.

Over the week, I spent every day in the lab, peeling back layers of muscle, labeling and pinning each one until the limbs looked like strange blooming flowers with petals of flesh. Finally, I came to a point where I needed to disconnect the arm from the axial skeleton to better facilitate working with it. Up to this point, I had been working on the body as a whole. The process of detaching a human arm from a torso was an experience unlike any other I had encountered. I was concentrating and noting the position and composition of the sternoclavicular joint, the makeup of the shoulder girdle and the manner in which it moved across the thoracic. At the same time, I couldn’t disregard the fact few people ever see a human body in this state of disarticulation. I reassured myself it was okay, alone in this lab with no fellow students to ease the sense of isolation, that I was part of a long tradition of artist-anatomists working with human cadavers.

We have such an estranged relationship to the dead in Western culture. This experience changed me personally as well as professionally. It calls to mind the Buddhist practice of Cemetery Contemplations. In this tradition, the practitioner will seek out and contemplate various kinds of corpses in burial grounds. It is intended to aid in breaking down attachments to the self and the physical world. I thought of the Bon Chod Tantric practitioners who go to the burial ground at night to meditate with the corpses. I thought of the women in ancient Greece washing and anointing the dead, tenderly working the magic of the underworld for their souls.

At the end of the week, I flew back to Northern California. I had filled sketchbooks with drawings and notes and taken several reference photos. My mind was racing with all I had learned and the greater understanding I had gained from the experience. A couple days after my return I waiting in a queue in my car, when suddenly I was crying. I had to pull the car off to the side while I sobbed uncontrollably in a parking lot. I sat there for half an hour weeping in grief and thankfulness to people whose names I would never know.

As I sat in my car, I reflected on all those people whose bodies I’d spent the last week with. Not being a doctor, what they taught me would never be used to save a life. I would never diagnose or treat an illness. Instead, I hoped that I might honor that gift by bringing some beauty to the world with art, or perhaps by helping some future student to a greater understanding and appreciation of the human form. I hope I do them honor by my respect and by sharing with you the wonderful things they showed me.

“Conscience is no more than the dead speaking to us.” ― Jim Carroll

LeDespencer 2019