Fin de Siècle Paris was a city in the midst of transformation. Life was in transition and nothing could hold its mercurial energy at bay. The previous century had seen the French Revolution and the Industrial Revolution, and what would come to be known as the first wave of feminism was in full swing. The so-called “New Women” were becoming increasingly visible, feminists striking out to claim their independence. The old notions of religion and morality were being turned on their heads and progress left no convention untouched.

In the midst of this maelstrom of social upheaval there could be found a darker, more esoteric current. At the end of the age of Enlightenment a new-found devotion to the esoteric and the occult welled up from the popular consciousness. This was the age of the Symbolists, the Decadents, Spiritualism, Rosicrucianism, and Satanism. From this milieu a new type of woman emerged, a woman who would not be defined by piety and obedience. These were women who embraced the spirit of the rebel angel; these were satanic feminists.

These satanic feminists didn’t necessarily all identify as diabolists, nor did they all embrace a unified ideology of satanism. Rather, they responded to a zeitgeist, a general movement which rejected the old norms, embraced the idea of Lucifer as liberator, emancipated women from the patriarchal bonds of the church, and upended the narrative of Eve as original sinner. Instead, they claimed the Romantic ideal of Satan as a symbol of rebellion against the unjust.

Problematic women have always been characterized as witches. Just a few decades earlier Jules Michelet had published his La Sorcière, the first book to characterize witches as women in rebellion against a stifling oppression. The symbol of the Witch often comes to represent cultural anxieties concerning women. These women discovered a strength and agency in putting on the vestments of that which is feared, recontextualizing the satanic woman into something empowering. This is a movement we see emerging once again, this time across race and class lines with young women rediscovering their power in the context of witchcraft. So it was in that new age of liberation and emancipation when some found reason to embrace the Witch, gladly take the apple, and wear the serpent, proudly aligning themselves with the adversary.

In 19th century Paris, with its preoccupations with sexuality, death, and evil, no figure cut a more sensual and diabolical presence than that of Hyacinthe Chantelouve, the fictional femme fatale and satanic initiatrix of J.K. Huysmans‘novel, Là-Bas. Madame Chantelouve was the dark reflection of the emancipated “New Woman.” She seemed to represent in equal parts all that traditional society feared, yet secretly desired. A divorcee, living openly in a polyamorous relationship, she sexually pursued men without reservation and relished in enacting the most ornate of blasphemies through her involvement with the Parisian Satanic underground. In the novel it is Mme Chantelouve who serves as the guide for the narrator’s descent into the depths of the occult demimonde. So influential was the character of Madame Chantelouve that she became something of an aspirational figure among those women who sought to foster a more sinister allure. Symbolist poet and dandy Jean Lorrain noted in his book Pelléastres; le poison de la littérature that:

“There was no brasserie in Montmartre, or studio in Montparnasse, where a little model, with eyes dilated by morphine and ether, did not rise at the mere mention of Huysmans’ name, to exclaim: ‘Chantelouve, that’s me!’ “

This influential character did not spring fully formed from Huysmans’ imagination; quite the contrary, as a Huysmans was naturalist author and protege of Émile Zola. Like his teacher, Huysmans strove to base his characters in reality and Hyacinthe was no different. She was the very thinly veiled likeness of a former lover, the bohemian mystic and poet Berthe de Courrière.

Upon Clésinger’s death she inherited his fortune. She hired the decadent author Remy de Gourmont to write a memorial of her late husband and the two quickly became lovers. Her affair with Gourmont was passionate and intense. Berthe would serve as the inspiration to his novels Sixtine and Le Fantôme, a feverish tale of religio-sadistic eroticism. His passionate love letters charting their affair would be published as “Lettres a Sixtine.” Gourmont was absolutely enthralled with Berthe and he described her in his Portraits du Prochain Siècle:

“She is a Kabbalist and occultist, learned in the history of eastern religions and philosophies, fascinated by the veil of Isis, initiated by dangerous personal experiences into the most redoubtable mysteries of the Black Art. A soul to which mystery has spoken – and has not spoken in vain.”

Berthe would become muse and literary agent to Gourmont, assisting in managing his affairs. Together they would entertain other members of the Parisian literati at their apartments. J.K. Huysmans spent many an evening listening to Berthe’s tales of those “dangerous personal experiences,” stories which had an huge impact on his most notorious novel, Là-Bas.

Rumors about Berthe and her occult predilections were rampant. She was said have sought out young priests to seduce or shock with her explicit confessions. The decadent author Rachilde, herself a bisexual, cross-dressing iconoclast among women, recounted walking along the Seine with Berthe who removed a small embroidered bag from her skirts and from it produced consecrated communion wafers to feed to stray dogs.

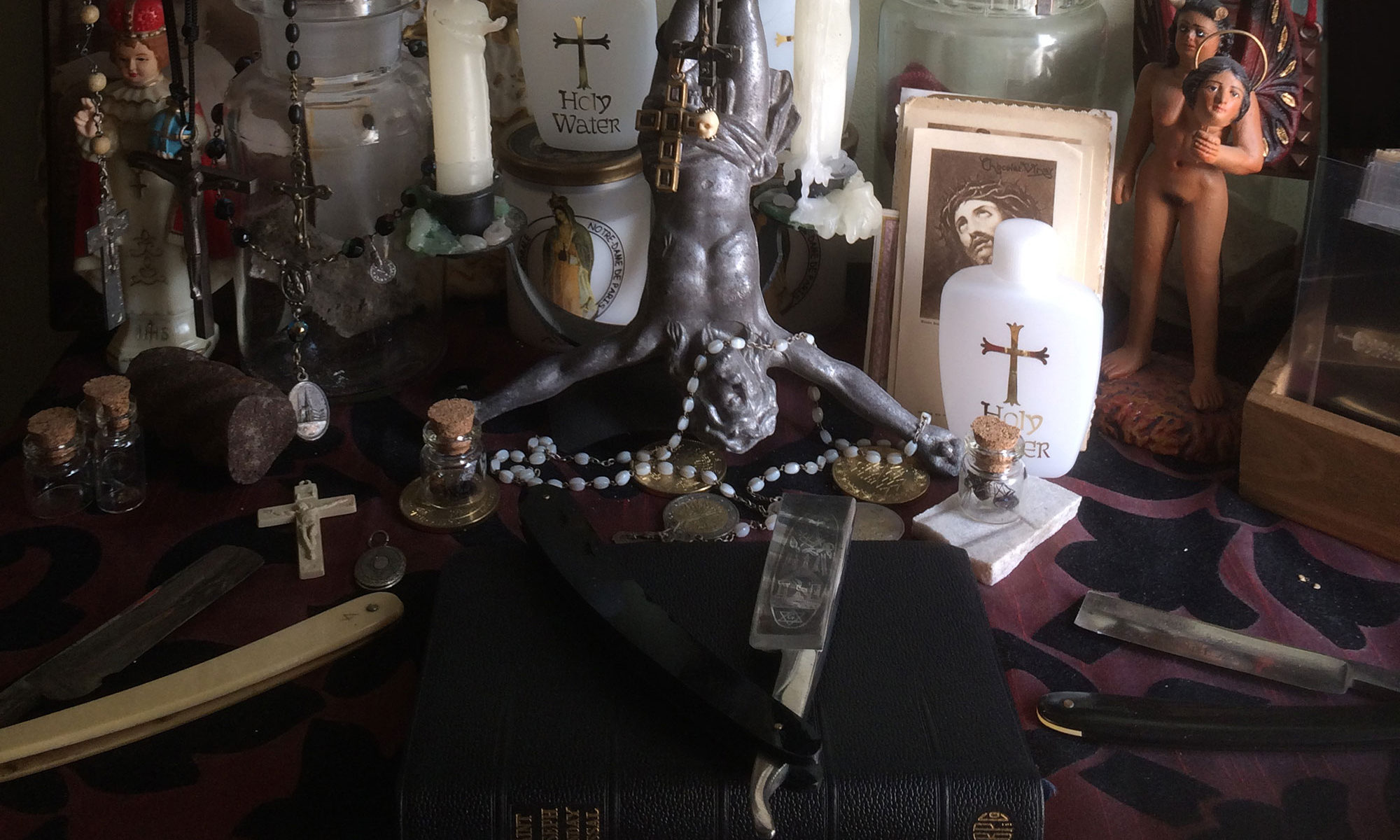

Every aspect of Berthe’s life was immersed in the decadent and the taboo. Belgian Symbolist Henry de Groux described the unique decor of her apartment as “…the most diverse thing I had ever imagined–the taste of this world half-pagan, half-Catholic, or so-called such. Altar cloths, religious objects adapted to most unexpected locations, monstrance, corporals, dalmatics, candelabra with multicolored candles lit in mysterious corners of shade, near a beautiful lectern the works of Félicien Rops or the Marquis de Sade. The scent of benzoin, amber, rose essence suffocating dose alternate with those of incense. ”

Berthe was a poet and author as well. Through Gourmont she became closely linked to the legendary journal Mercure de France. She would supply several pieces for the magazine, the most notable being her Néron prince de la science, a scathing prose poem which railed against abuse in the name of science at the hands of doctors like Jean-Martin Charcot and his psychiatric cult of Hysteria. This would be a topic of great personal concern to Berthe, as she herself would be committed twice in her lifetime, first at Bruges in 1890 and later in 1906.

Berthe embraced the life of the socialite, with connections to every corner of the Parisian occult and literary worlds. It was through these connections J.K. Huysmans found so much fertile ground for Là-Bas. It was Berthe who introduced Huysmans to the infamous defrocked priest Abbe Boullan, inspiration for the character Dr. Johannes. Boullan would find himself at odds with the Vatican over his ideology and along with his companion and lover, the nun Adèle Chevaller, ran The Society for the Reparation of Souls. Together they taught a mystical religious ecstasy that involved sexual union with the Saints, Mary, and ultimately Jesus himself. Rituals were said to involve blood, urine, and group sex. Berthe would describe Boullan to Huysmans as “a charming man.”

Berthe also alerted Huysmans to a certain Louis Van Haecke, priest at the Basilica of the Holy Blood in Bruges. Van Haecke enjoyed an ominous reputation as a satanist and blasphemer. He was notorious for frequenting the company of occultists and defrocked priests in Paris. He was also rumored to perform Black Masses. Some even said he tattooed crosses on the soles of his feet so as to have the pleasure of forever treading on the sign of salvation. Van Haecke would serve as Huysmans’ inspiration for the evil priest Canon Docre.

Most biographers of the era do a terrible disservice to Berthe. They write her off as a “neurotic” or “a nymphomaniac,” adopting all the jargon of the era used to disenfranchise and dismiss. While citing her two instances of incarceration they ignore how easy it might be for a woman to find herself committed for displaying the same peculiarities that the average bohemian man could flaunt without concern. Women in the era were confined for much less. However, the most infuriating affront to her memory is in how a particularly heartbreaking episode is relayed which relates to the circumstances around her incarceration at Bruges.

In 1890, while in Belgium, Berthe was found nearly naked and shivering in the bushes near the home of Louis van Haecke. When discovered, she recounted her escape from the local priest who was in fact a satanist. The police did not believe her and had her committed in the local asylum. It would be a month before Remy could secure her release. Subsequent biographers cite this as an example of her instability. In reality, this looks shockingly like a woman fleeing a sexual assault. Years later, when the skeptical author Herman Bossier was researching this episode, he was surprised to discover the records of her testimony to the police as well as the records of her testimony in the asylum Saint-Julien had both mysteriously disappeared.

Like so many women of her time, she is barely remembered, and usually for her connection to the men whom she inspired. Despite their posturing, many authors associated with the Decadent movement tended toward a more cerebral sin, a delectatio morosa, rather than living an actual life in the extreme. They would often mine the lives of others for inspiration just as Huysmans mined the wealth of Berthe’s experiences to flesh out his own fictional world. When he was done, she was discarded and her influence diminished.

Her lover Remy passed away on September 27, 1915. She buried him in Clésinger’s tomb, her two loves resting together in the family plot. It was a mere nine months later that Berthe would join them both. She was interred in the same crypt, a ménage à trois among the cold stones of Père Lachaise Cemetery. Her name is sadly absent from the stone.

13, March 2016. Madeleine LeDespencer