“Give me something I can regret forever.”

These words, whispered as prelude to a brutally tragic murder, sum up the oppressively terrifying world of Sauna. It is a world in which regret, sin, and debasement take on all the qualities of religious sacraments and redemption is found in a place far removed from any merciful god. It’s a gnostic world, flawed at its very fiber, in which the only escape is through the black hole of sin itself.

Sauna, also known as Filth, or under the unfortunate alternate title, Evil Rising, is a 2008 Finnish film directed by Antti-Jussi Annila. While the title may seem unassuming, the promotional materials feature the hauntingly stark image of a 16th century European soldier standing knee deep in stagnant water before a looming white structure. The image is fascinating; a massive white façade, like an ominous negative image of Kubrick’s Monolith, sitting both temporally and spatially displaced in the black waters. It is out of space and out of time. This structure would prove to be the titular Sauna; atemporal, ominous, and iconic in its representation of an encroaching other in the otherwise picturesque marsh.

Sauna has been described as: “a cruel horror film bathing in the Finnish sauna culture, in the no-zone between Christianity and Paganism.” Classifying Sauna as a horror film is limiting, in as much as one might consider Pasolini’s Salo or Jodorowsky’s Santa Sangre to be horror films. Sauna does draw on many of the narrative conventions of the ghost story. The influence of M.R. James is especially felt in the manner in which “ghosts” are presented, not as diaphanous and ethereal beings but rather corporal, wet, and shuddering horrors. In many ways Sauna transcends the tropes of the genre to become something more, a work of art which is, at its core, philosophically disturbing. Annila calls into question any convictions we might have about transgression and forgiveness and paints a world in which the only constant is the reality of an ubiquitous and ever-present transgression without any hope of redemption.

Set in 1597, Sauna tells the story of two brothers who, following a long and bloody war, are part of a commission marking a border between Finland and Russia. After commandeering the home of a man and his daughter, they kill the father and leave the young girl locked in a cellar to die. This act haunts the youngest brother, as they are his first exposure to crimes of war. For the eldest, the murders are merely one more cruelty weighing on his already strained conscious. After fleeing the homestead they are followed by a terrifying apparition of the girl, her face pouring with an endless river of black filth.

Upon rejoining their companions, the brothers come across a Russian-Orthodox village in the centre of the swamp. It is here they come across an old disused sauna. The village was once inhabited by Russian Orthodox monks, but they long since disappeared, leaving all the trappings of their faith cast off and locked away in an old shack. The strange inhabitants of this village –peasants dressed in spotless white garments– confide in the soldiers that this sauna possesses special properties; those that venture inside find their sins are washed away in a place “outside religion.” The story centers on how each member of the party navigates their own past transgressions and how the Sauna itself feeds on their regrets.

Annila’s narrative focuses on filth and cleansing as something both physical and spiritual. From the opening shot, in which we see a crystal clear mountain stream start to run red with blood, the film focuses on themes of guilt and the process of becoming stained. There is no monster lurking in the shadows here. The monster in Sauna is our own sense of sin and our desire to be free from the evils we do to one another. Likewise, the horror of Sauna is the suggestion that the redemption we might seek is not what we have come to expect. By questioning our ideas of morality and innocence Sauna unsettles the viewer by snuffing out any sense of hope or purity. Annila crafts a worldview in which the very act of existing is to be stained. It’s a sort of original sin in the absence of any benevolent gods. As one character states early in the film,

“What is filth? Filth is the mark that’s left when two things touch each other. It’s the very proof that one thing has touched another. Therefore filth is the material that all our memories are made of…”

The world expressed in the film presents itself as entirely composed of metaphysical and literal filth. It elevates the abject to the level of the numinous. Cleansing is achieved by passing across the borders between worlds into a liminal space represented in the Sauna. This operation is almost Gnostic in its conception, harkening back to the early heretical Christian sects, many of which conceived the nature of the world to be irreversibly flawed. To these Gnostics the creator god was a vain and evil demiurge who trapped our pure spirit in this hell of creation. To them, transcendence was the only escape. In many ways Annila’s film could be considered as a Gnostic horror film. All of creation, all matter was inherently broken exists in a perpetual state of uncleanliness and imperfection. The whole of creation is, in essence, soiled. Those who seek to escape it via the sauna find themselves transformed by the ecstasies of their guilt.

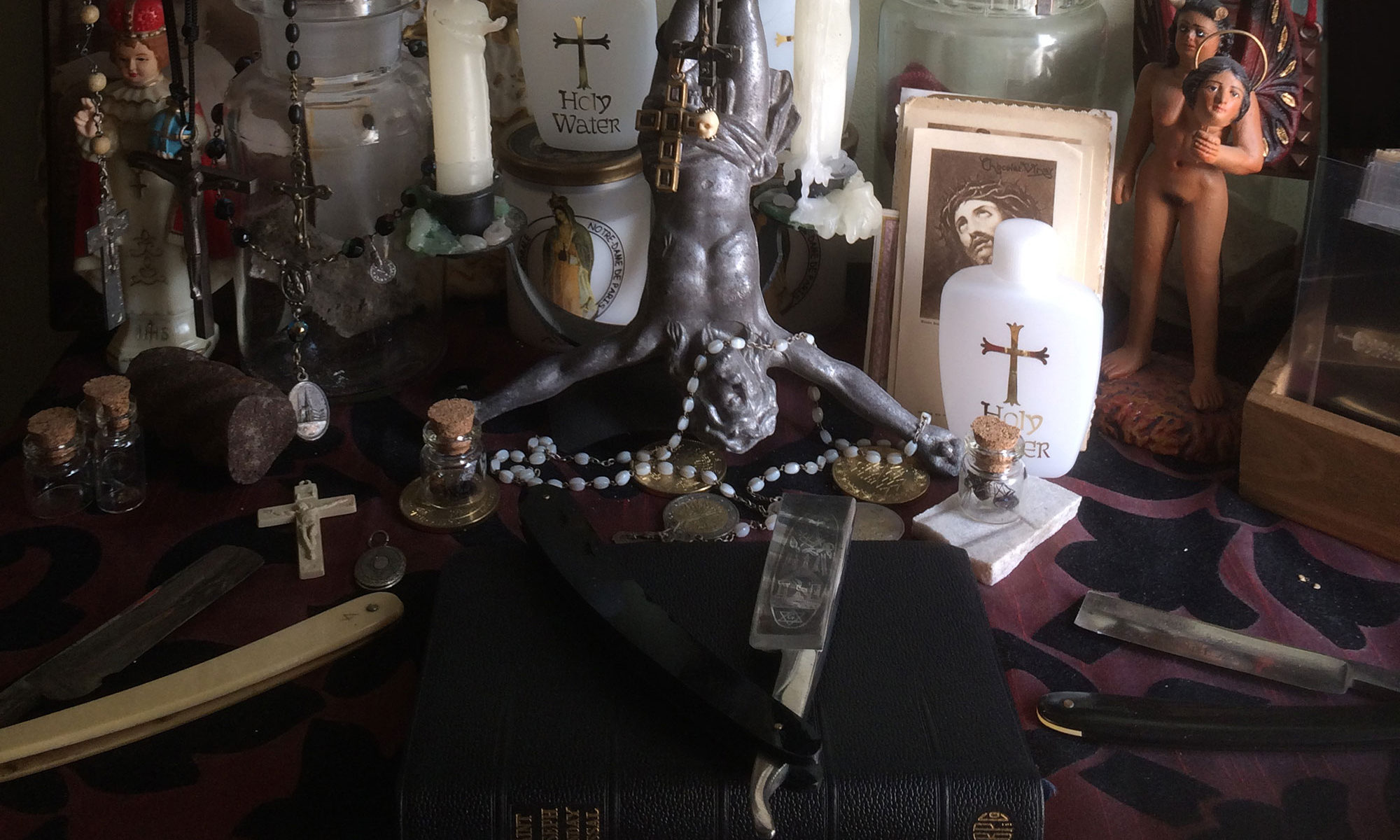

In many ways Annila’s film is the most successful Lovecraftian film I have ever encountered; this despite the filmmakers making no effort to directly reference Lovecraft or his mythos. Too many times popular culture conflates Lovecraft with tentacles, Cthulhu, or kitschy cultists, while neglecting the true genius of the man’s oeuvre. The true horror of Lovecraft is the terror of the sublime; the sense of self being overwhelmed and subsumed to the presence of a vastness which dwarfs and destroys you. Humanity is meaningless in Sauna. Theology has been left to decay among disused icons of the Virgin in the storage sheds of that strange swamp village. Here the world is unmasked as a terrible machine that runs on pain and generates refuse.

Part of what makes the film so unique is the subtle interweaving of various cultural traditions into its own mythology. To fully appreciate the film one must understand the place of the Sauna in Finnish culture. In Finland, the Sauna is a sacred space; it comes with its own elaborate rules of decorum and respect. It’s intended to be outside the confines of everyday life where bathing takes place. By seating his horror in such a privileged liminal space Annila adds a deeper sense of blasphemy.

There are suggestions as well of ancient Finnish conceptions of the soul and afterlife. The ancient Finns believed the soul was composed of multiple autonomous parts. The original word for the life force or spirit was löyly which has now come to mean the hot air inside the Sauna. The Itse was the aspect of the soul which might be called the sense of self or self-image. Sometimes ghosts would be said to come back and steal the Itse from a living person, leaving them a pallid somnambulist shell.

The manner of cleansing that takes place in the film’s sauna calls to mind a cross-cultural and ancient practice known as sin eating. A sin eater is an individual or entity which consumes the sins of the recently deceased, thereby freeing their soul. It is a practice that is found from the Meso-American to the ancient Semitic. Even Jesus of Nazareth is considered by some to be a kind of sin eater. Most striking is the Aztec goddess Tlazolteotl. As the patron of steam baths, child birth, adulterers, and filth, Tlazolteotl comes to devour the misdeeds of the dying. She is the ultimate goddess of the liminal, of borders and transformation. With all these suggestive links, the sauna here becomes much more than a bathhouse, it comes into focus as a locus of various traditions much older and more chthonic.

Sauna is a very unique yet woefully overlooked film. It is a thought-provoking tapestry of syncretic mythologies evoking an existential horror that will not be easily forgotten. The film manages to raise many questions leaving you with a lingering sense of mystery and unease. As one character remarks as they first lay eyes on the titular structure in the cold swamps,

“Perhaps it’s not a Sauna, but only appears to be one because we can’t comprehend what it is…”